- Home

- Gemma Amor

White Pines Page 15

White Pines Read online

Page 15

Mac’s voice wobbled. ‘And what about my town, my people?!’

I thought then that he might fling himself at me, at the very least throw a punch in my direction, but he didn’t. Instead he stared at Matthew and I with barely concealed hatred, then turned his back on us.

It didn't make much difference if he hated us, I knew that. The only thing that mattered was that, for now, we were alive. That we had to stay alive, survive this event. I was convinced that sticking even one toe into the triangle would result in death, or worse. The cairn was safe, for now.

That was all that mattered.

21. Waiting

And so we waited for something to happen.

Waited for the air to still, for something else to signal a return to normalcy.

We waited in vain.

‘Look!’ Luke saw it first, and pointed.

Miserably, we huddled at the base of the cairn, and watched as the air quivered and snapped.

There is nothing left to take, I thought, for the unreliable air reminded me of snapping jaws, hungry for prey. You’ve taken it all.

But the Island wasn’t trying to steal anything away, this time. It was trying to send something back.

Whatever it was appeared and disappeared so rapidly we couldn’t make out anything beyond a quick blur, extinguished in seconds. I had the impression maybe of wheels, and possibly handlebars, like a bicycle, but it was over so soon I couldn’t be sure. The triangle was a live thing, flickering and shuddering constantly. It gave us all headaches to look at, so eventually we stopped trying to make sense of it, and began to stare at our own feet, cushioned by safe, green blades of grass that didn’t move unless we willed it so.

I began to work on a theory.

White Pines had gone, that much was obvious. But to where? To a place that was not far from here, not far at all. I could sense it. A place behind a curtain, behind a veil.

And the divide between that place and this was weak, flimsy. Weak enough to pass through, weak enough to cross over.

So the town was trying to come back, but only parts of it made it safely across the divide, safely beneath the veil. These were parts that the other place couldn’t hold onto, for reasons I couldn’t fathom. They popped into this reality, and were promptly snatched back into the other one.

As theories went, it was wild, I knew.

But then, I was only working with the evidence given me.

Headaches began to build. We were thirsty, and the sun was growing stronger. I felt my face burning, turning hot. The cairn cast a little shade, and we followed it about, like the shadow from a sundial, trying to keep out of the increasingly harsh glare.

Midday hit, and the cairn’s shadow disappeared completely, the harsh noon sun affording us only a thin, dark crescent moon inside which we could not fit. The silver-haired woman took off her floor-length skirt, exposing worn, practical underwear and surprisingly lean, brown legs. She used her skirt as a sunshade, and left enough space for Luke to huddle beneath it with her. I swallowed back a lump in my throat when I saw this.

Mac had taken to marching around the cairn, hugging the stones tightly so he did not go near the edge of the green grass border. He walked as if marching to sentry duty, his shotgun resting on his shoulder. He was a man of action, and sitting still waiting for death or change apparently didn’t suit him. In that respect, I sympathised.

There had been no time for pleasantries before. Now, I had all the time in the world. I seated myself quietly next to the silver-haired woman, introducing myself.

‘I’m Megs,’ I said. In another time or place, I would have offered her my hand. Now, the gesture seemed absurd. My name would have to be enough.

To my relief, she returned the courtesy. Her name was Rhoda. The teen’s name was Johnny, and he was Mac’s nephew.

Mac refused to make eye contact, or acknowledge me in any way. He just kept marching around the cairn, constantly moving, keeping ahead of his own existential dread.

We sat in shared silence for a while longer, and then I spoke up.

‘The trees,’ I said, and I didn’t know who I was asking, or why it was so important to ask that question there and then. ‘The pine trees. They aren’t...from around here, are they?’ My voice cracked with thirst, and I coughed and spluttered into my fist.

When I had recovered, I expected Rhoda to answer, but it was Mac who spoke up. He didn’t stop walking for a second, but he was at least talking to me. I considered that progress.

‘They are not. Indigenous.’

I nodded. ‘Didn’t think so. I’ve never seen anything like them.’

Mac did another loop of the cairn. Then, he stopped, finally. Sweat rolled down his temples, and he licked dry lips. He seemed actually happy to be distracted, and his eyes took on a faraway look.

‘This Island had trees a long, long time ago. Pines, probably, larch. But it was barren when I bought it back from the government. Under quarantine for forty-eight years, it was.’

‘Bought it back?’

‘Aye, the land belonged to my family before the army bought it.’

I had completely forgotten about the anthrax. So had Matthew. We glanced at each other, and despite everything, a tiny flash of something almost approaching amusement sparked. How our priorities had changed.

Mac continued. ‘Not much of anything left here after the army and the scientists finished with it. They took all the topsoil away in 1986. Dumped formaldehyde and seawater all over the place to decontaminate it. I bought it back off them for five hundred pounds, once they’d finished. Place was barren, then. My family should never have given it over in the first place. Shame. Shame.’

He shook his head. Something flashed into view on the charcoal ground to our right, beyond the green circle, and vanished a few seconds later. Was it me, or were the appearances getting longer? I felt like I could almost see that last object, as if it had hung around for longer than the blink of an eye.

‘With the topsoil gone, we needed something for growing. Root networks bind the soil. Stop it from washing away.’

I’d picked up on it earlier, but I realised again that Mac wasn’t from these parts. He didn’t have the lilting Highlands accent I had expected. His voice was husky, distinct.

He continued. ‘I ended up bringing my own soil, clean, uncontaminated, nutrient-rich. Best graded topsoil I could find, brought up from the South. We spread it everywhere, planted that stand of trees. First thing we did, before anything else. Keep the wind at bay. Bind the soil better. Stop run-off. Keep nosey-parkers like you away from our community.’

I swallowed, and shook my head ruefully. Trees or no trees, my destiny had always been this Island. God, I was thirsty. Matthew, of the same mindset, stuck his tongue out. It was coated in a white, sticky film. He made gargling noises to try and get some saliva to move about in his mouth. I let my eyes travel across the triangle, to the barcoded ring of pine trees beyond.

Now Mac had started, it seemed he couldn’t stop. ‘Fastigiate Eastern White Pine, or Pinus strobus Fastigiata.’ He enunciated the Latin carefully, and I had an impression that he was well-educated. Horticultural college, maybe. Perhaps he just read a lot. ‘Native to America. I had them shipped over especially, like the soil. A couple thousand of them, young saplings, all hand planted, most by me, some by Rhoda, the rest by the community as it grew.’ Rhoda and Mac exchanged looks, and I saw love there, and understood their relationship better with that look.

Matthew put his tongue back into his mouth, then stilled. He had spotted something else in the triangle, but I still didn’t want to look.

‘Only they didn’t grow quite like they were supposed to,’ Mac continued. ‘They grew fast. Unnaturally fast, although this suited us, so we didn’t complain about it. And they came up white, and skinny. Little tufts of needles on top. Fastigiata has a blue colour to the foliage, normally. Grows dense, like a Christmas tree. We thought maybe it was something in the soil. But they give us…’ Mac trai

led off, slapped a hand against his thigh in frustration. ‘Gave us some privacy.’

I had more questions. So, so many more questions. Why had he chosen to build a community here, with the history it had? Hadn’t they noticed the disparity between the size of the Island and the available space they magically had to build upon? What and who were the cairns for? Did he know about the tunnel? Were there more?

All these questions would have to wait. Because I felt a hand in my hair, patting the top of my head to get my attention.

Matthew hovered by my side, zombie-like. ‘Look,’ he said. The air shivered like a sick animal all around us. Then, I saw it, lying on the ground. It was a child’s hula-hoop, candy striped in white and red. It lay there for a full thirty seconds before disappearing.

I’d been right about something, at least.

After that, Matthew sank into a deep hole of depression as the atmosphere, his own helplessness, and shock at what had happened began to weigh on him. He roused himself every now and then to check on me, before retreating right back into himself.

Luke sat cross-legged on the grass next to Rhoda, keeping himself well back from the edge of the green strip as I’d instructed him to do. He pulled blades of grass and small sprigs of heather out of the ground with his small, deft fingers, and rolled them up into spongy balls in the palms of his hands, then made a pile of these in front of his feet. It looked as if he were subconsciously mimicking the cairn that loomed behind him. He sniffed every minute or so, and his lip wobbled frequently as he thought about his missing parents, his vanished house.

It grew brighter, and warmer still as mid-afternoon rolled in. Our timid, halting conversation dried up. We waited as the agreeable weather mocked us, and the pale pines looked on.

Nothing else happened.

Until Matthew raised a shaking hand, and pointed.

‘There,’ he said, in hushed tones.

We all leaned forward intently.

The air flickered again, like a heat shimmer on a hot tarmac road.

And inside the perimeter of the burned triangle, about ten feet away, something materialised.

Rhoda let out a strangled cry, and made to get to her feet. Johnny grabbed her, held her down.

‘Don’t!’

‘But that’s mine!’ She said, and we looked.

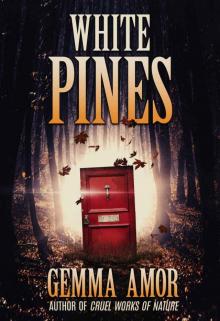

It was a red door, or at least, the top two-thirds of a red door, still mounted inside its rustic door frame. There was nothing else attached to it, no wall, no masonry. No lintel. Nothing behind, or around it.

Just a door.

It stuck out of the ground at an odd, unnatural angle, reminding me of my Granny’s headstone in Laide cemetery, leaning drunkenly as if the earth were subsiding beneath it. Only that wasn’t right. The door wasn’t sinking into the ground at all. It had simply materialised half-in, and half-out of the soil. As if the door had been sent back from wherever it had been, only to return to the wrong place. Instead of sitting at ground level, the bottom of the door now sat a foot or two below the earth.

A number also hung on the door, the number ‘4’. A simple brass door-knocker gleamed against the shiny red gloss paint. I stared, and bit back a wild urge to laugh. The door was so incongruous, so unnatural against the context of its empty, blackened surroundings that the scene reminded me of a Salvador Dali painting. A surreal, ridiculous nightmare.

‘Where is the rest?!’ Wailed Rhoda. ‘Where is the rest of my house?!’

Johnny held onto her.

It was a good question. Where was the rest of the house?

Where was the rest of White Pines?

The urge to laugh died as quickly as it had arisen. ‘I want to leave now, Matthew,’ I whispered, and I saw him nod.

Wanting, and being able to, were two different things, however.

Thirty seconds later, the door vanished.

22. Behind the veil

The sun travelled across the sky, bored by our helplessness.

We saw other things flit in and out of existence with an alarming, erratic rapidity. A child’s bike. A chair. A long-handled wooden shovel. A steel bucket. Another door, green this time. It looked a lot like Luke’s front door.

‘What’s happening?’ The boy asked, for the hundredth time, as an upended tricycle juddered into life, then dematerialised. ‘What’s happening?’

‘I wish I knew, kiddo,’ I replied, also for the hundredth time.

‘Is my Ma okay? And Daddy?’

Matthew heard this, and I saw his spine stiffen. He crouched down so that he was at the same eye-level as Luke.

‘I don’t know what’s happening, pal. I wish I did, so that I could explain it to you. But we’ll try and find out, won’t we? We’ll try our best for your Ma and Dad. We just have to stay brave, okay?’

Luke blinked back tears, and Matthew awkwardly ruffled the boy’s hair. Then he spotted something glinting under the boy’s shirt collar.

‘What’s that?’ He asked, gently.

The boy pulled out a long silver chain. On the end of a chain, a pendant swung. ‘My Ma made it for me,’ he said. ‘It’s my lucky charm.’

‘You hang onto that,’ Matthew said, then. ‘You hang onto it, tight.’ He was thinking that it would be all the boy had left of his family. I bowed my head.

Mac spoke up.

‘It’s the town, you know. Trying to come back.’ He said it in a dull voice. It was an eerie echo of my earlier thought process, and I found myself nodding.

‘What?’ Matthew looked at the man, not understanding what he meant.

But I understood.

Three more hours passed, three hours in which we didn’t move. We watched the nightmare display of White Pines flotsam and jetsam, washing into existence on a tide of mysterious, indiscriminate energy, and floating back out again into the unknown moments later. It was exhausting and unnerving to witness. Thankfully, only inanimate objects came back. No people, or animals. I was more than grateful for this. I didn’t want to see what would happen to a person who came back in the wrong place, buried to the waist in soil, or stuck under a rock, or worse. I didn’t want to have to look at their faces when they disappeared again.

Mac, having tired himself out, now stood like a statue below the rocks, staring out at the triangle with a lowered brow. He reminded me of an eagle sighting prey. Every time the air flickered, he flinched, but that was the only sign of distress he allowed himself. Everything else about him was still, composed, as if he were forcefully holding all the pieces of himself together. As a leader does, I thought. What must he be feeling? What must they all be feeling?

A burgeoning need to urinate made itself known to me as the day wore on. I ignored the pressure building in my bladder for as long as possible, but after thirty minutes of squirming, I knew I couldn’t hold it anymore. I signalled to Matthew that I needed to relieve myself. He roused himself, nodded, and sank back into his brown study. Mac continued his watch, back straight, eyes almost lost under his brow. Rhoda cried quietly into her hands. Johnny sat miserably on the ground beside her, head down, not wanting to engage with the world anymore.

Luke kept his hands busy, making little grass bullets to add to his pile. Every now and then he fiddled with the pendent around his neck, then tucked it carefully back under his shirt, patting it to make sure it was safe. He’d taken Matthew’s words to heart.

I edged around the base of the cairn, to the opposite side of the rock mound, the side that faced the most northerly point of the triangle. I thought about the spiritual consequences of urinating on, or near, a sacred stone cairn, but I had no choice. Our bodies don’t stop being our bodies just because the world is going to shit around us.

Besides, I figured I had already pissed off the god beneath the tree as much as I was able.

I sighed, pulled down my trousers, and crouched. A trickle of piss made its way downhill as I relieved myself, snaking through the green strip and across into the black, where, predictably, it vanished, like a thin, wet worm that had been uncer

emoniously sliced in half with a sharp knife.

My business finished, I stood up again and rearranged my clothes. They now felt days old, sweat-rough. My body ached. I looked at my hands, which couldn’t quite get to grips with the zipper of my jeans. They shook as I held them out before me. The stub of my little finger seemed more pronounced than ever against the bleak, seared land behind.

Beyond the edges of the triangle, a circle of pine trees with flawlessly white bark watched my every move.

I hated them.

I turned to rejoin the group. As I did so, something caught my eye. Movement. A suggestive spasm, the air nictitating, telling me that something else was crossing back from behind the curtain. I waited for it, and when it materialised, finally, I gasped. Tears gathered in my eyes.

The Island had heard me, and called my bluff.

This time, it had sent back a wall, or a section of one. A drystone wall. About five feet long, by four feet high. Grey stones tessellated.

Amongst them, strange, brown, bedraggled things struggled, and squawked.

‘Birds,’ I breathed.

They were stuck in the wall. A whole flock of them, embedded into the stonework like nothing I’d ever seen before. Wings and feet twitched. Feathers trembled. Tiny, beady eyes darted about frantically. The birds were still alive, although dying fast. The wall had come back in the wrong place. Or the birds had. Or both had, simultaneously, smashing into each other to create this unholy spectacle, this macabre embrace.

‘Little Brown Spuggies, my Ma used to call them.’ Mac’s voice came from behind me, and I jumped. How long had he been there?

We stood, aghast at the spectacle.

‘Like flies trapped in amber,’ he continued, and he was exactly right.

Like bodies in beach-glass, I thought to myself. Like a cherry tree in crystal.

Mac ran his hand across his eyes and coughed.

‘What if it’s not birds, next time?’

‘What?’ I didn’t fully process what he was saying, at first.

‘What if, next time,’ Mac repeated, echoing aloud what I’d kept to myself earlier, ‘It’s not birds?’

White Pines

White Pines